You may remember from the last piece:

...if the guy looks away I feel so for the woman and can't help thinking: it isn't the way things have to be. It is so avoidable.

And maybe you saw (here):

It is true some of the guys in Buenos Aires were lovely to dance with and many had qualities I wish we saw more of here in Europe. Still, I would not want to mislead you. Who would have thought a look could be such a dangerous thing?

Those first ten days in Buenos Aires turned me upside down. I lost my compass in everything, my sense of identity in a way. While I enjoyed and relaxed in those days, they were also unnerving. One of the main ways I lost my bearings was in accepting guys in the milongas. I watched a lot before so doing but even so I did not accept invitations to dance the way I would in Europe.

That night I went to Obelisco, a well known, good traditional milonga popular among people my age and older. The venue is good and the music from Dany and Vivi is the best around. I was given a prime seat in the centre of the women's section on the long side directly in front of all the single guys. I never did work up enough courage to ask for a more discreet seat in Spanish. Still, bingo! Pretty soon I saw the guys I was looking for. They were all tall, all sitting together. We had seen each other off and on in other milongas. Time went by and they did not invite me. A milonga started, a fast dance with a syncopated rhythm. Men the world over, but especially in Buenos Aires, usually choose to dance tango with a new partner, not milonga. While nothing is set in stone careful men tend to choose tracks they know are likely to work well with a new partner.

I do not know exactly what happened. I just know what I thought happened and the effect, in the way that small things can be devastating, was just that. Foolishly I looked towards one of the guys in that group with whom I still wanted to dance. I knew that girls never invite guys in Buenos Aires and do so at their peril in other places. Did I do something? Suggest something? Did my eyebrow move a quarter inch? Perhaps I was so used then to dancing the guy's role that what I thought my girl look was misconstrued as a guy-type invitation. Perhaps they had just seen me looking and had had enough. Or maybe I saw something not even intended for me. But I thought I saw one of the guys raise his finger and wag it unmistakably.

My first reaction was shock and to look away.

When I did look up or elsewhere, compounding my problems, I accepted, randomly and without thinking, the next invitation that came my way. Of course I knew not, ordinarily, to accept a guy you have not seen dance, and had not been doing so. I knew especially not to do so in unfamiliar circumstances where you are not entirely your own steady self. In these circumstances it's best not to feel giddy with embarrassment and two glasses of Argentinian 'champagne'. What's needed is a sense of groundedness and ease and to stick to tried and tested behaviours that you know result in good dancing.

As soon as we stood up I saw that the man was small. Very small, with terrible teeth. He looked up towards my nostrils after each dance, grinned and enquired, more as statement than question, if everything was fine. I nodded, mutely. The tanda - four tracks - lasted.

I see now the politer, more respectful thing might have been to make an excuse. That is what I might have done or certainly considered in the UK had that situation somehow come about. But I did not know how things worked in Buenos Aires. I did not know what the consequences would be of walking out of a tanda mid-way through and based on no obvious insult. In milonga culture doing so is a metaphorical slap in the face of the man. It means I cannot bear this and I am so insulted by your behaviour or your dancing that you will never invite me again. The milonga is a very visual place. Everybody is watching. Everybody sees. What would the effect be of doing something so public, so humiliating to a man, especially in a macho culture? Had he, really, done anything wrong? He hadn't groped me, or done anything unseemly. He had done nothing worse than men do every day - tried their luck with a girl, within acceptable parameters. And I'd agreed.

When I sat down this double mortification spread over me and tears brimmed so helplessly that I could not look anywhere or move in case they spilled and everyone saw what indeed an absurd and imprudent giant baby I was. Being strung out from culture shock, fatigue, heat and home sickness was taking its toll.

As soon as I could bear to move and safely I went to the ladies. Usually women walk through the men's section to get there, the men moving aside and taking the opportunity to make eye contact with a view to future dances. But I scrambled around the backs of chairs on the women's side, tripping over bags and shoes. I knew I should leave but something stubborn dug in. I went back and sat for tanda after tanda - for two hours in fact - deliberately accepting no one. I looked anywhere but at the men in the cortina - the few minutes of non-tango music that signifies the end of one tanda and time to sit down and catch your breath before the next. It had never felt longer. I sat torturing myself, proving - why? - that I could sit there. Telling oneself - still less someone else - to relax is never a successful strategy so to tell oneself to enjoy watching the dancers and listening to the music was perhaps optimistic but for a few moments at a time, it worked. When I felt I’d persecuted myself enough I left the salon and went, towards midnight to a pre-arranged meeting with a friend at another milonga, the gay one, which was much more relaxed and just what I needed right then. I should have gone earlier!

But something unplanned and unexpected did happen in those remaining two hours at Obelisco. In my flaming embarrassment I decided to start re-listening to my instincts. These, especially regarding who and when to accept, had been on hold as I had taken on information and advice from books, articles and other people on how dancing tango in Buenos Aires is different. Quite simply, it takes time to adjust to how different things are in Buenos Aires. Compounding matters, the milongas can be large venues and busy. There are so very many unfamiliar men and for a while they can all look very similar - same clothes, same age, same height, same specs, same keyfob by their pockets. And yet in a three week stay you do not have much time. That is the problem but you just can't force these things. This return to instinct was one of the best decisions I made there. Nothing much changed, overtly. I expect I still looked the same, danced about as much, acted more or less similarly but once I took that decision and moved on from that evening it was what made me relax into the trip and into the milongas.

Even so, indignity piled upon indignity. In the foyer of Nuevo Chiqué the following week I was chatting to Bob and Viv of Tango Gales. An Austrian ex-pat or well-established visitor came out and we were introduced. With teutonic directness she said:

Oh, you’re Felicity. I’ve heard about you.

Oh? I tried to say politely, smiling nervously. I know these things show. How could she have heard about me? The people out dancing tango across the city every night number at least in the hundreds.

Ja! she said. I heard about a very tall foreigner who accepted a dance from a guy who had his face in her boobs and all you could hear was ze grunting.

Gossip and Chinese whispers. I crumbled and confessed my mistake.

But dear, she said kindly. You should have stopped dancing as soon as you felt uncomfortable.

But he didn’t do anything, I said. 'Do' is understood in Buenos Aires in the context of what men can do to women on the dance floor. He was just...small. And we were not...compatible.

It does not matter, she said. As soon as you felt uncomfortable!

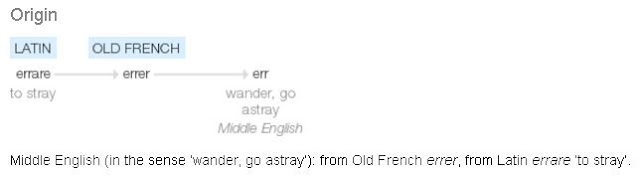

On a side topic of etymology. "Devil" is from "diabolo", "throw to the side" / "leading sideways" (cognate to "diagonal")

ReplyDelete