This is the third consecutive piece on tyranny inspired by the novel 'The Feast of the Goat' (2000) by the Peruvian writer, Mario Vargas Llosa.

We will come on to why sinvergüenza (a noun describing a person without shame) was so apt for the whole Trujillo family and at least one of the descendants today.

But what is the psychological process that allows a tyrant to bypass the shame that stops most people behaving with total unaccountability and pride in that? It is because they live in a parallel a world, a construct, a fantasy, in which they are saviours, God, enlightened among self serving, idle fools They are right and everyone else is wrong and that is how they justify their actions. It is an act of convincing themselves and then of pulling the wool over other peoples eyes, or, if they are powerful enough, brute coercion of others. The seeds of tyrants are in the people you know who are never wrong.

The ends, for them, justifies the means. Actually, once you have persuaded yourself of so much, why admit any error at all? Leave no chink! Your enemies will only exploit it! By this logic there is nothing wrong with the means either. In the pitiless world of the tyrant, means and ends are all fine when acting against some perceived evil - anything goes. Everyone who manipulates, coerces, bullies, intimidates and uses violent means for their own convenience, greed and power has, necessarily, to justify it to themselves in some way. Only a madman would admit they do it because they like it. On the contrary, the tyrant often sees themselves as performing a service that others are too weak to do themselves. If spoils come their way in the process, well, it's only well-deserved.

Like narcissists the tyrant is unable to see, still less accept, the reality of themselves in a wider moral context.

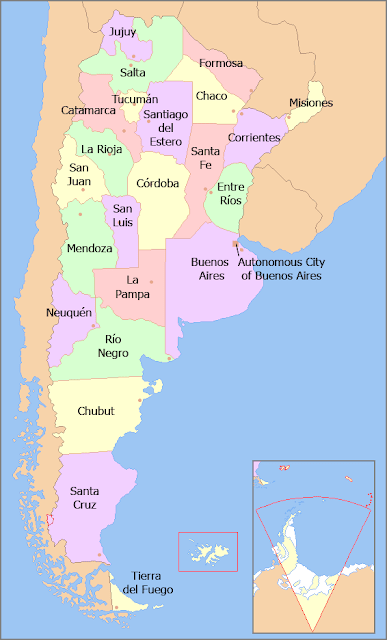

It is often said a liar is found out, by their colleagues, their family, their children. My husband is prone to saying this. It calms his spiking blood pressure. I have always had good blood pressure, until just lately. But are they found out? The novelist, in the case of Trujillo, did the accounting, the reckoning, for the long term. This book is world famous, one of the great novels on dictatorship and yet so few people know about the Trujillo dictatorship. Was it in Peru? said a thirty-something Spanish/Ecuadorean at the weekend. I asked a smart Argentinian in his late twenties what dictatorships he was aware of on the continent. The Argentinian military junta he replied, and Pinochet. The same seems to go for an awareness of the history of their own continent in general. When I mentioned the War of the Triple Alliance between Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil against an over-confident Paraguayan leader that wiped out 70% of the men of that country, at the end of the nineteenth century, the thirty-something PhD student from Chile had never heard of it.

So how liars, tyrants, found out or accountable? Consider Israel: nearly an entire country brainwashed from infancy and backed by the worlds strongest power even while it bombs an imprisoned and defenceless civilian population and all of their infrastructure into oblivion. Perhaps that national tyrants, the individuals are eventually found out in the wider context, but the everyday tyrant in miniature who steals and controls under the cover of paperwork and lies, less so.

In many cases, the deformity of tyranny is passed on to the children. It is the model the children grow up with. Ramfis was easily as sadistic as his father, perhaps more so but, since the definition of a tyrant is at least a caricature of a bully, it was almost a foregone conclusion that Trujillo would both spoil and disparage his sons for the wastrels they largely were. Radhamés, the younger son ended up tortured and killed, a pawn of the Colombian drug cartels. The parents, though, will educate the children into “looking out for the family”, which is just another way of saying self-centered. On a larger scale this is the them-and-us ugliness of nationalism.

The whole Trujillo family was implicated in the dictatorship. Doubtless they convinced themselves that they, too, were doing this for the good of the country. The wider Trujillo family were certainly motivated by greed. But in Trujillo himself, he had so much, he didn’t need more. His greed was sexual and it was about power. Money buys you things but once you are sated, if you still want more, money is really about personal power. Trujillo, like many dictators, had all the characteristics of a narcissistic: from the charisma, to the obsession with medals and grandiose honorifics.

For Trujillo, power was represented by virility.

" Rugía y robaba. ¿Por qué le ponían tantas pruebas? La cruz de sus hijos, las conspiraciones para matarlo, para destruir la obra de toda una vida. Pero no se quejaba de eso. Él sabía fajarse contra enemigos de carne y hueso. Lo había hecho desde joven. No podía tolerar el golpe bajo, que no lo dejarán defenderse. Parecía medio loco, de desesperación. Ahora sé por qué. Porque ese güevo que había roto tantos coñitos ya no se paraba. Eso hacía llorar al titán ¿Para reirse, verdad?"

"He shouted and begged. Why was he given so many trials? The cross of his sons that he had to bear, the plots to kill him, to destroy the work of a lifetime. But he wasn't complaining about that. He knew how to beat flesh and blood enemies. He had done that since he was young. What he couldn't tolerate was the low blow, not having a chance to defend himself. He seemed half-crazed with despair. Now I know why. Because the prick that had broken so many cherries wouldn't stand up anymore. That's what made the titan cry. Laughable, isn't it?"

There is a memorable artwork of a prick symbolising power and sexual violence

A tyrant's symbol exposes them for what they are. It is always about them, their hold on power, what represents power to them. He should have had a symbol less prone to vagaries than his own ageing, flimsy prick. It is interesting that that a prick is chosen as the symbol. Used the way he used it, to rape women, it represented power over more vulnerable people. Because he cultivated a macho society in which women were objectified, diminished, stereotyped and used, other men rallied round that symbol of so-called strength.